The Price of Neglect: Assessing the Consequences of Underfunding Earth Measurement

The Invisible Thread Holding Our World Together

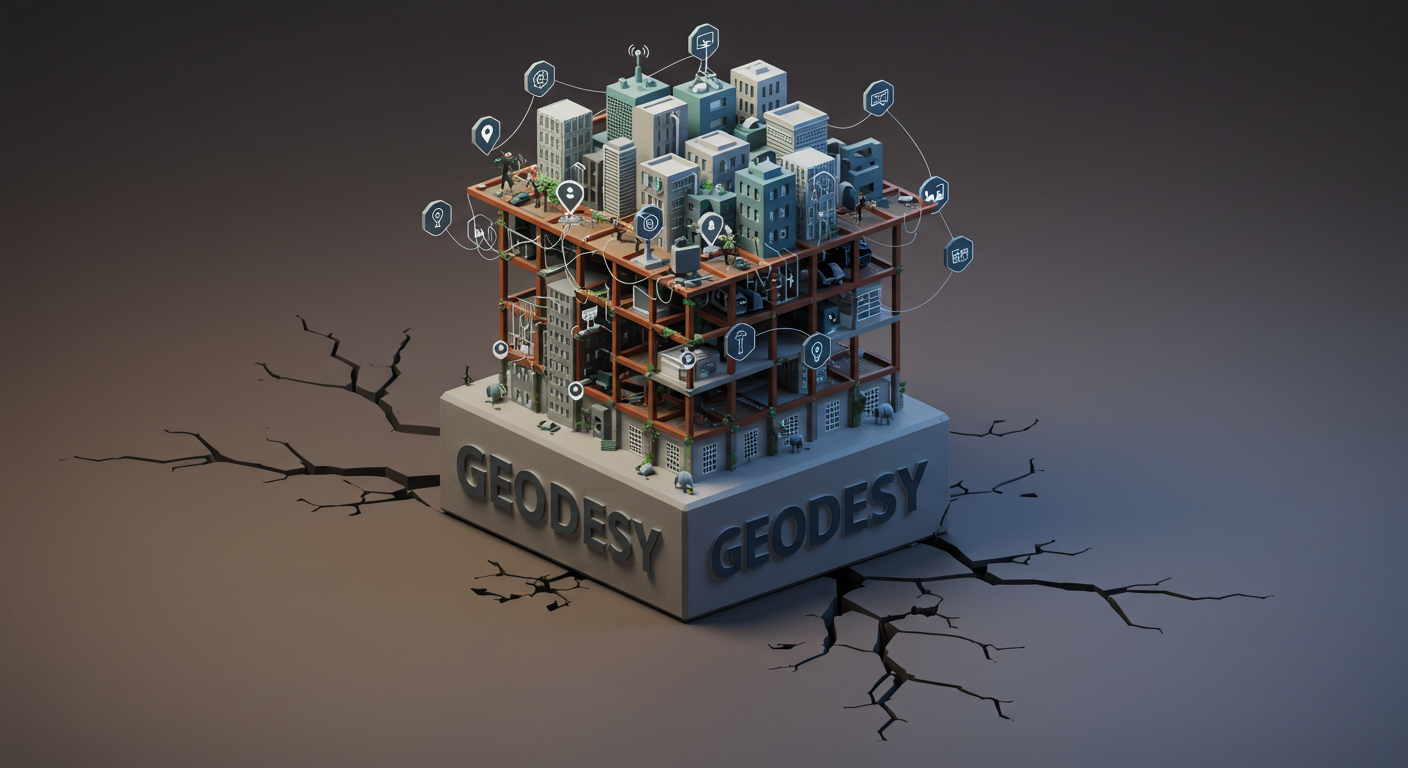

Imagine a world where your phone can't guide you, where planes struggle to navigate safely, where the power grid flickers towards instability, and where monitoring the health of our planet becomes a blurry guess. This isn't science fiction; it's the potential reality if we neglect a fundamental, yet largely invisible, science: geodesy. It’s the discipline dedicated to meticulously measuring and understanding our dynamic Earth – its shape, its wobble in space, its gravitational heartbeat, and how these change, constantly, relentlessly. Far from a niche academic pursuit, geodesy provides the invisible threads that weave through the fabric of modern life. It's the bedrock upon which our navigation systems, communication networks, satellite technologies, and even the stability of our power supply depend. Indeed, the critical nature of this science and the challenges it faces, particularly in the United States, have been previously highlighted, defining what constitutes the modern 'Geodesy Crisis.' (Read on the US Geodesy Crisis Here)

This report, however, shifts the focus to pull back the curtain on the profound and potentially devastating consequences—technical, logistical, and deeply human—that would unfold globally if we allowed investment and operational updates in geodesy to falter. It’s not just about maps or coordinates; it's about maintaining the vital signs of our planet's spatial and temporal framework. The continuous stream of measurements, the constant refinement of models like the Terrestrial Reference Frame (TRF) and Earth Orientation Parameters (EOP), aren't optional upgrades. They are the essential, ongoing maintenance required to prevent the systems we rely on every single day from unraveling. What happens when the ground truth shifts beneath our technological feet? The answer involves a cascade of failures with implications reaching into every corner of our society and economy. This is the story of the unseen pillar holding up our world, and why letting it crumble is a risk we cannot afford to take.

In the realm of nuclear existential threat, we have the Doomsday Clock. In the world of global infrastructure, we have the Geodetic Doomsday Clock. It measures the time remaining before the "unseen pillar" of modern life, the Terrestrial Reference Frame (TRF), degrades beyond the tolerance of the systems it supports. As investment in geodetic science stagnates and workforce pipelines dry up, the hands of this clock are moving closer to a systemic midnight.

The Unseen Foundation: Geodesy's Role in Modern Infrastructure

Defining Geodesy: More Than Just Lines on a Map

At its heart, geodesy is the science of asking fundamental questions about our planet: What is its exact shape? How does it spin and orient itself in the vastness of space? What is the nature of its gravitational pull?¹ Crucially, it recognizes that the answer to these questions isn't static; our Earth is a living, breathing, shifting entity.¹ Although geodetic data powers national systems and services, its reliability is rooted in a globally coordinated foundation. It is built from shared measurements, standards, and reference frames that transcend borders. While its roots lie in the essential tasks of surveying and mapping—pinning down locations to create reliable maps and define property lines²—modern geodesy paints a far richer, more dynamic picture. It views Earth as an intricate system, a complex interplay between the solid ground beneath our feet, the vast oceans, the swirling atmosphere, and the frozen cryosphere.⁴ This understanding provides the essential scaffolding needed not just for mapmakers, but for a vast spectrum of Earth sciences and countless practical technologies that shape our daily lives.⁴ At its core, geodesy is the science of where things are—not just in an absolute sense, but in relation to everything else. It underpins our ability to navigate, build, respond, protect, and understand. We’ve always needed to know where we are, and we always will.

From this intricate science flow the data products that silently power our world:

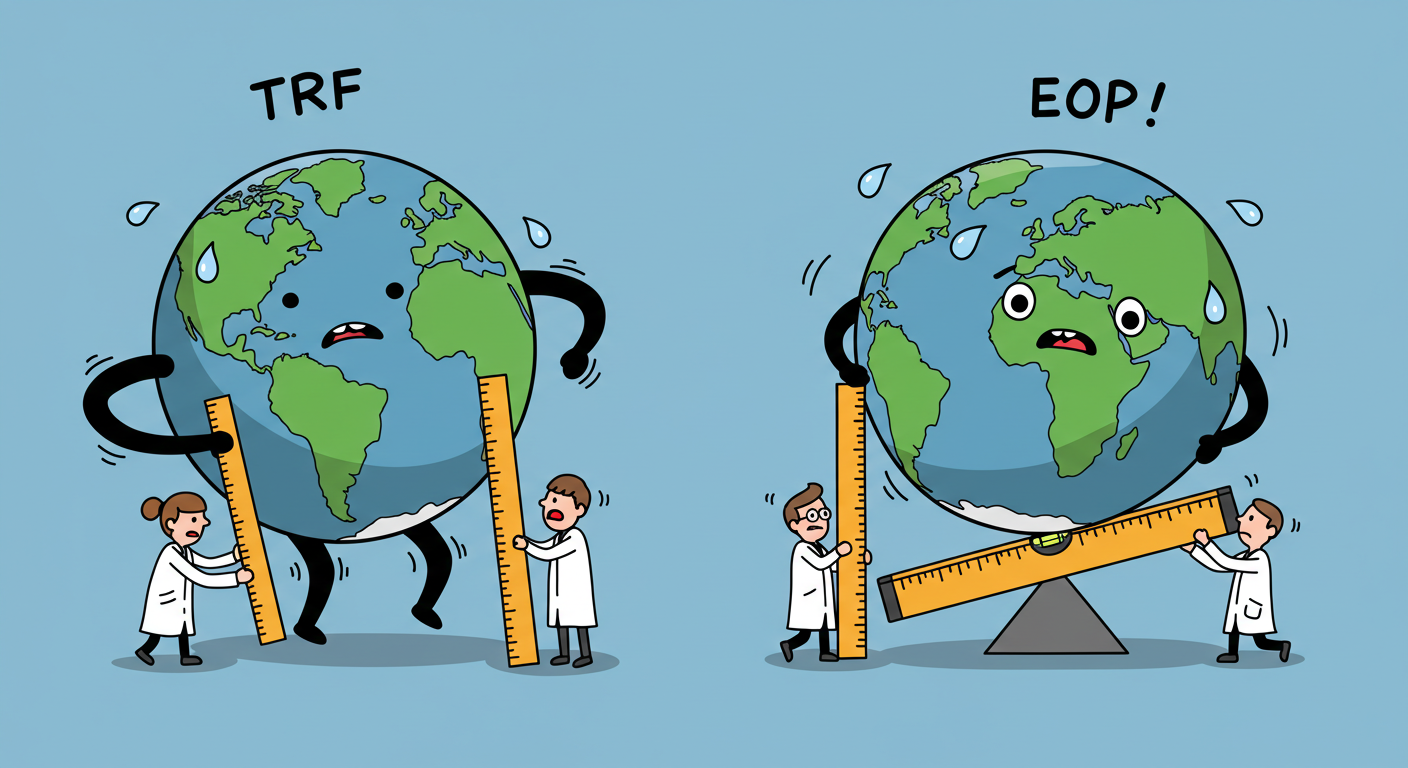

Reference Frames: Think of these as the ultimate, globally consistent address books, like the International Terrestrial Reference Frame (ITRF). They don't just list locations; they track how those locations move and change over time, anchoring everything from satellite orbits to property boundaries in a reliable system.⁶

Earth Orientation Parameters (EOP): Our planet doesn't spin perfectly smoothly. EOPs precisely describe its complex wobble (polar motion), the slight variations in the length of our day (UT1-UTC), and the dance of its axis against the backdrop of the stars. This data is the crucial translator, linking our Earth-bound coordinates to the near-absolute reference of space.⁶

Gravity Field Models: These detailed maps of Earth's gravity aren't just academic curiosities. They define what "level" truly means (the geoid, approximating mean sea level), allowing us to understand water flow and determine meaningful heights. They are also indispensable for predicting the paths of satellites orbiting our planet.¹

Precise Coordinates: Geodesy provides the ultra-accurate locations for the critical ground infrastructure—like the tracking stations for GPS satellites—that forms the backbone of our positioning systems.²

But the Earth refuses to sit still. Its dynamism—the slow creep of continents, the sudden jolt of earthquakes, the ebb and flow of tides and groundwater—means these fundamental parameters are in constant flux. Geodesy provides the tools not just to measure, but to understand these changes, moving far beyond a static postcard view of our planet.⁴ This constant motion necessitates continuous observation, analysis, and updating. The geodetic foundation isn't something built once and forgotten; it requires perpetual vigilance and upkeep. To neglect this maintenance is to knowingly allow the systems built upon this foundation to degrade, risking the stability we take for granted.

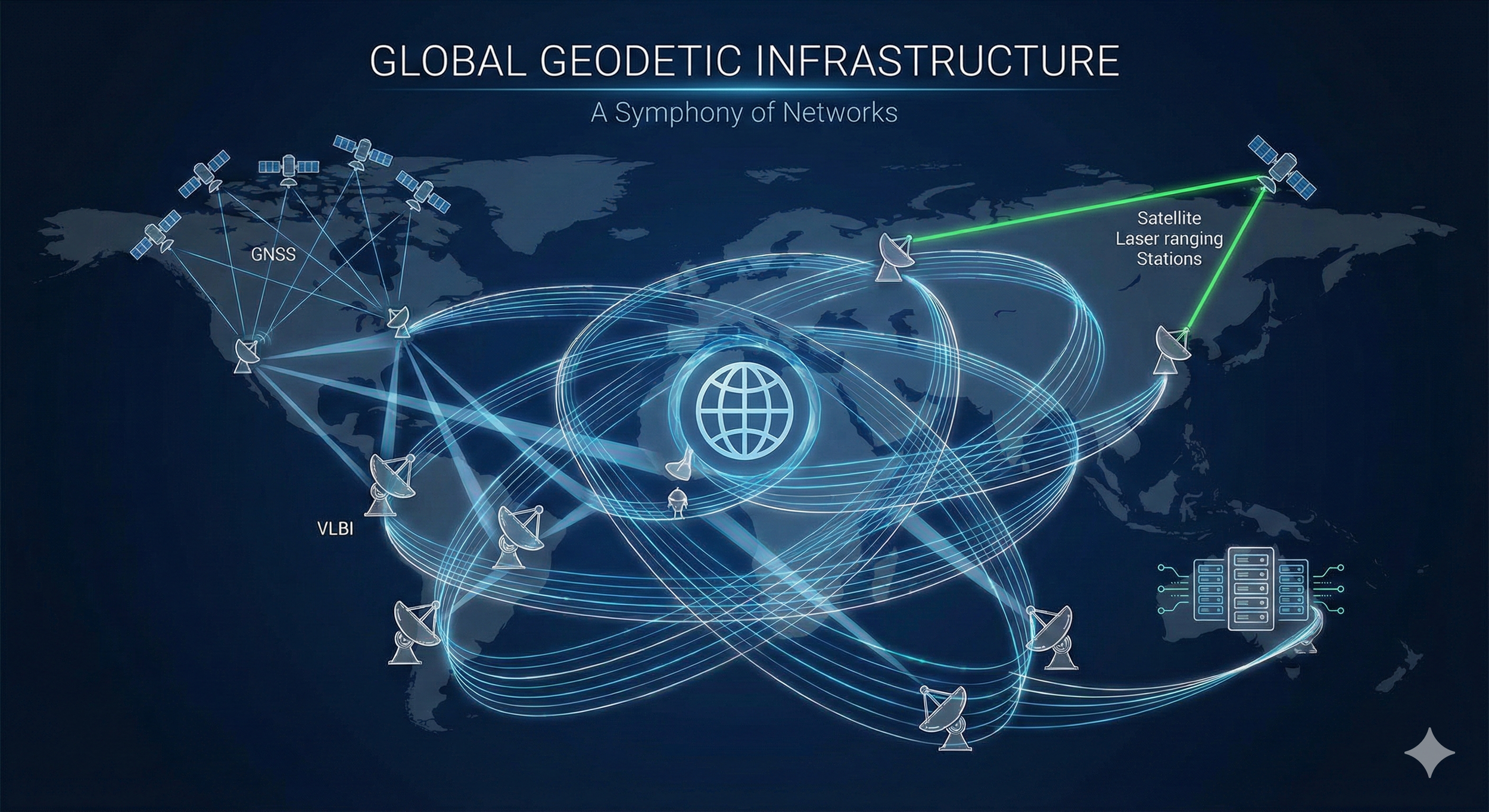

The Global Geodetic Infrastructure: A Symphony of Networks and Services

This global geodetic fabric is not the work of a single nation but a testament to sustained international cooperation. Organizations like the International GNSS Service (IGS) and the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS) form a worldwide “system of systems.” They voluntarily pool data and expertise from hundreds of agencies to produce the indispensable global reference frames and Earth orientation parameters. This collaborative spirit ensures that the geodetic foundation is robust, consistent, and freely available to all, fostering scientific progress and supporting critical applications worldwide. However, this reliance on shared responsibility is also a key vulnerability. If major contributors, such as the United States, reduce their participation or investment, the integrity of the global geodetic system suffers, weakening the shared foundation on which all nations rely. This aligns directly with the UN's emphasis on the need for shared commitment to maintain this critical global infrastructure.

The impact of such a reduction becomes clear when considering the specific, tangible components that constitute this global system:

Terrestrial Reference Frames (TRF): The TRF is the invisible stage upon which almost all positioning and navigation activities play out.⁷ The gold standard is the ITRF, a marvel of precision and stability. Its creation is a feat of data fusion, meticulously combining measurements from different "space geodetic" techniques: Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) listening to distant quasars, Satellite Laser Ranging (SLR) bouncing lasers off satellites, the familiar signals of Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS), and the Doppler tracking of DORIS satellites.⁷ Each technique uses a global network of ground stations. International services, operating under the banner of the International Association of Geodesy (IAG)—like the International VLBI Service (IVS), the International Laser Ranging Service (ILRS), the International GNSS Service (IGS), and the International DORIS Service (IDS)—act as the diligent collectors and initial processors of this raw data.⁷ Finally, the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS) takes these inputs, weighs them, combines them, and produces the official ITRF. This defines not just the Earth's center of mass (geocenter), but its scale, orientation, and crucially, how these evolve due to relentless forces like plate tectonics.⁷ National systems, like North America's NATRF2022 (which replaces the older NAD 83), are carefully tied to this global standard to ensure seamless consistency.¹

Earth Orientation Parameters (EOP): EOPs are the language describing Earth's intricate rotational dance.⁸ They tell us exactly where the North Pole is pointing relative to the crust (polar motion, x and y) and relative to the stars (celestial pole offsets, dX and dY). They also track the tiny difference between time measured by Earth's rotation (UT1) and the atomic clocks that define Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), reflecting variations in our planet's spin speed (Length of Day, LOD).⁷ Why does this matter? These parameters are the essential key to translating coordinates and movements between the Earth-fixed TRF and the quasi-inertial Celestial Reference Frame (CRF) used for satellite orbits and astronomy.⁸ Like the TRF, EOPs emerge from the combined analysis of space geodetic data, orchestrated primarily by the IERS.⁷ Accurate EOPs are non-negotiable not just for pinpointing locations, but also for any application needing to precisely relate atomic time (like the UTC on your phone) to the actual rotational phase of our planet (UT1).¹⁸

Gravity Field Models: Geodesy maps the subtle variations in Earth's gravity. These models are essential for defining the geoid, the true baseline for elevations.¹ Thanks to accurate geoid models, often built from a mix of ground measurements, airborne surveys (like the US GRAV-D project¹), and dedicated satellite missions, the height reading from your GPS (relative to a simple mathematical ellipsoid) can be converted into a physically meaningful height above mean sea level—telling you which way water will actually flow.¹ Moreover, knowing the gravity field precisely is absolutely critical for calculating accurate satellite orbits, as gravity is the primary conductor directing their paths through space.⁴

International Services and Collaboration: The Human Network: This intricate system works because of a truly global, human endeavor. The IAG and its services (IGS, ILRS, IVS, IDS, IERS), along with initiatives like the Global Geodetic Observing System (GGOS), coordinate the efforts of hundreds of agencies across the planet.⁷ The IGS alone is a voluntary partnership of over 200 organizations in more than 100 countries, pooling resources and data.¹⁰ This isn't just helpful; it's fundamental. Achieving the required accuracy, consistency, and reliability demands this global teamwork.²⁶ If any major player reduces investment, stops participating, or hoards data, the entire system weakens, impacting everyone, everywhere. The deep interconnectedness—where better TRFs improve EOPs, which in turn improve satellite orbits used to refine gravity models¹¹—further highlights that only a holistic, collaborative, global approach can sustain this vital infrastructure.

The Necessity of Continuous Measurement: Keeping Pace with a Restless Planet

Our Earth is anything but a static marble. It's a dynamic system, constantly reshaping itself, breathing, and shifting on timescales from seconds to millennia.⁵ Geodetic techniques are our planetary stethoscopes and scales, essential for observing and quantifying these changes—changes that directly impact the very foundations of navigation, timing, and how we monitor our world.²

Consider the forces relentlessly at work:

Plate Tectonics: The ground beneath us is moving. Lithospheric plates drift, typically at speeds of centimeters per year, constantly rearranging the continents and ocean basins.⁵ This means the coordinates of everything on the surface, including the geodetic stations themselves, are continuously changing.¹² Where plates collide or grind past each other, stress builds and releases in earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, causing sudden, dramatic shifts in the crust.⁵

Earth Rotation Variations: The speed of Earth's spin isn't perfectly constant (affecting the Length of Day and UT1-UTC), and the axis it spins around wobbles relative to the crust (polar motion). These variations arise from a complex exchange of momentum between the solid Earth, the oceans, the atmosphere, and even the molten core, influenced by the gravitational tug of the Sun and Moon.⁵ Recent unexpected accelerations in polar motion have even been shown to introduce biases in our measurements of vertical land movement.³¹

Tides: The Moon and Sun's gravity doesn't just pull on the oceans; it rhythmically deforms the solid Earth itself (Earth tides) and influences ocean currents (ocean tides). This causes ground stations to move slightly and introduces variations in gravity and Earth's rotation.⁸

Surface Loading: The shifting weight of water, ice, and air on Earth's surface causes the crust to flex. Atmospheric pressure changes, ocean bottom pressure variations, the movement of water through rivers and groundwater, and the immense weight of melting ice sheets and glaciers all deform the crust, alter the gravity field, and subtly change Earth's rotation.⁴ The slow rebound of the crust from the melting of ancient ice sheets (Glacial Isostatic Adjustment, GIA) continues to cause significant vertical land motion today.⁵

The inescapable truth born from this planetary restlessness is that our geodetic reference frames are not, and can never be, fixed monuments. Station coordinates are perpetually in motion.² Earth's orientation drifts continuously.⁸ The gravity field itself subtly morphs as mass is redistributed.⁴ Therefore, the work of geodesy is never done. Continuous measurements and the regular, relentless updating of TRF coordinates and velocities, EOP time series, and gravity models are not just best practice; they are absolutely essential to maintain the accuracy and integrity of the spatial and temporal framework our critical technologies rely upon.⁸ Using outdated geodetic parameters is like navigating with a map that's constantly warping—errors inevitably creep into positioning, navigation, timing, and our interpretation of vital Earth observation data. The geodetic foundation demands constant vigilance simply to keep pace with our dynamic home planet.

The Human Element: Why Expert Oversight is Irreplaceable

While we might imagine automated sensors seamlessly feeding data into powerful computers, the reality of maintaining our planet's geodetic health is far more nuanced and deeply reliant on human expertise. The notion that updating these critical measurements is a simple, push-button process dangerously overlooks the intricate judgments and collaborative science involved.³²

The Challenge of Data Fusion: Geodetic cornerstones like the ITRF and EOP aren't born from a single source. They emerge from the rigorous combination of data from fundamentally different techniques (VLBI, SLR, GNSS, DORIS).¹⁰ Each method possesses unique strengths, weaknesses, error signatures, and potential biases.¹⁰ Weaving these disparate threads into a coherent, accurate, and reliable whole requires sophisticated analysis, careful weighting of data, and deep expert understanding to avoid artifacts specific to any single technique.¹⁰ This complex integration, often orchestrated by international bodies like the IERS, is steeped in human oversight and scientific judgment.¹⁰

The Art of Quality Control: Raw geodetic data arrives noisy, potentially contaminated by instrument quirks, environmental interference, or simple blunders (outliers).³² While automated routines perform initial filtering, spotting subtle systematic errors or distinguishing genuine geophysical signals (like an earthquake's signature) from mere noise often demands expert interpretation.³² Statistical outlier detection isn't foolproof, especially with the complex data patterns common in geodesy.⁴² Deciding whether an anomaly is an error to discard or a significant event to analyze requires judgment informed by geophysics and intimate knowledge of the instruments involved.³⁴

Refining Our Understanding: Geodetic analysis leans on complex physical and mathematical models describing everything from satellite orbits and atmospheric delays to tidal forces and crustal deformation.³⁶ These models aren't static; they are constantly refined as our scientific understanding deepens and measurement precision improves.³⁶ Human experts are essential for interpreting the inevitable discrepancies between observations and models, pinpointing where models fall short, and developing new theoretical frameworks to better capture the intricate dynamics of the Earth system.³⁵

Responding to the Unexpected: Automated systems excel at handling the expected. But the Earth system can surprise us with sudden shifts, like rapid changes in polar motion or large, abrupt ground movements from earthquakes or volcanoes.⁵ Responding effectively—assessing the impact on the reference frame, adapting analysis procedures—demands swift expert intervention.³⁹ Furthermore, the observing system itself is constantly evolving: new satellites launch, instruments are upgraded, station networks change.¹⁰ Integrating these changes while ensuring the long-term consistency of our records requires continuous expert management.³⁸

The Power of Collaboration: The global geodetic infrastructure thrives because of the coordinated dedication of hundreds of organizations and thousands of experts worldwide, facilitated by bodies like the IAG, IERS, IGS, ILRS, IVS, and IDS.¹⁰ These services depend critically on the voluntary contributions of data, analytical skill, and scientific oversight from the international community.¹⁰ Setting standards, ensuring quality, combining results, and driving innovation are all fundamentally human-driven, collaborative processes.¹⁰ While artificial intelligence and machine learning are increasingly valuable tools for tasks like data screening⁵⁴, they currently augment, not replace, the essential need for human expertise, interpretation, and decision-making throughout the entire geodetic workflow.³⁴

In essence, safeguarding the accuracy and reliability of our planet's reference system is a continuous scientific endeavor. It demands constant vigilance, critical thinking, and expert judgment. It involves far more than passively collecting data; it requires a profound understanding of our complex Earth, the nuances of diverse measurement techniques, and the dedicated collaborative spirit of a global community of experts. Automation provides powerful support, but the core responsibility for the integrity of our geodetic foundation remains firmly in human hands.

Recent cancellations of rapid-innovation programs, such as the U.S. Space Force’s Resilient GPS (R-GPS), underscore a dangerous policy pivot. While intended to streamline budgets, ending these programs removes a critical "demand signal" for the next generation of geodetic scientists and PNT engineers. By reverting to legacy satellite models like GPS IIIF, the U.S. is choosing "Legacy Stability" over "Architectural Resilience," effectively stalling the workforce pipeline required to maintain the very ground truth these satellites deliver.

Consequences of Stagnation: The Cracks Appear in Navigation and Timing

The Geodetic Lifeline of GNSS (GPS, GLONASS, Galileo, etc.)

Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS)—the familiar GPS, Russia's GLONASS, Europe's Galileo, China's BeiDou—have woven themselves into the fabric of modern existence, guiding our journeys, synchronizing networks, and enabling countless applications. Yet, their remarkable precision and dependability hang precariously on the continuous health of the geodetic infrastructure.⁴ This reliance isn't trivial; it's fundamental.

Here's how geodesy underpins the satellites guiding us:

Terrestrial Reference Frame (TRF): GNSS operations absolutely require a precise and stable TRF, like the ITRF. This frame defines the exact locations of the global network of ground stations that track the satellites, and ultimately, the orbits of the satellites themselves.¹ The accuracy of your calculated position on Earth is fundamentally limited by how accurately we know the positions of those ground stations and the satellites referencing them.⁷

Earth Orientation Parameters (EOP): Knowing precisely how the Earth is oriented in space (via EOPs) is indispensable. It's the key to translating between the Earth-fixed frame (TRF), where your receiver sits, and the quasi-inertial frame (CRF), where the satellites' orbital motions are calculated and predicted.⁸ Without accurate EOPs, connecting the satellite's position in space to your position on the ground becomes guesswork. Furthermore, parameters like UT1-UTC are vital for applications needing time tied specifically to Earth's rotation.⁴

Precise Orbits and Clocks: The magic of GNSS relies on knowing exactly where each satellite was and what time its onboard atomic clock read at the precise moment it sent its signal. International services like the IGS use data pouring in from a global network of high-precision GNSS receivers (whose locations are known thanks to the TRF and EOPs) to compute and distribute ultra-accurate satellite orbit and clock information—often achieving centimeter-level orbit accuracy and timing precise to fractions of a billionth of a second.¹

Atmospheric Modeling: The Earth's atmosphere bends and delays GNSS signals, introducing significant errors. Geodetic techniques, including the analysis of GNSS signals themselves, play a crucial role in monitoring and modeling these atmospheric layers (ionosphere and troposphere), allowing us to compensate for these delays.⁴

Any error in these foundational geodetic inputs—the TRF's accuracy, the EOP values used, the models underpinning orbit calculations—propagates directly into the final position calculated by your GNSS receiver. The largest gremlins in the system are typically errors in the satellite's assumed orbit (contributing perhaps ~2.5 meters of uncertainty) and errors in its clock (~2 meters), alongside atmospheric delays.⁶⁰ The accuracy of those orbit and clock components is directly governed by the quality of the geodetic processing performed by global services like the IGS.¹⁰ Therefore, allowing geodetic measurements and updates to stagnate isn't just a scientific lapse; it's a direct path to degrading the accuracy and reliability of the GNSS systems millions rely on daily.

Scenario 1: One Week Without Updates – The Predictive Edge Dulls

What happens if the constant stream of geodetic measurements and analysis suddenly stops? After just one week, the initial impacts ripple outwards, primarily affecting those living on the cutting edge – applications demanding real-time precision and relying on predicted geodetic parameters.

EOP Predictions Start to Stray: Earth's rotation is complex and somewhat unpredictable over longer timescales.¹⁷ Our ability to forecast EOPs accurately degrades rapidly. Within about four days, errors in predicting the pole's position can reach roughly 1.7 milliarcseconds (mas), while errors in predicting the Earth's rotational phase (UT1-UTC) can hit 0.2-0.3 milliseconds (ms).¹⁵ After a full week, these errors inevitably grow larger.¹⁵ While services like the IERS issue predictions weeks ahead⁶³, their reliability quickly fades.¹⁵ This primarily hurts applications needing immediate, precise EOP knowledge – think navigating spacecraft between planets or perhaps some highly specialized real-time GNSS correction services requiring the utmost accuracy.²⁰

Real-time High Precision Suffers: For the average user relying on standard GNSS for navigation (accurate to several meters), a week's pause likely goes unnoticed. However, high-precision techniques like Precise Point Positioning (PPP) or Real-Time Kinematic (RTK), which achieve centimeter-level accuracy by using real-time or predicted orbit and clock corrections implicitly dependent on recent EOPs, could feel the first tremors. Accuracy might slip from centimeters towards decimeters or worse, depending on how sensitive a specific system is to those growing EOP prediction errors. The sharp edge of precision begins to dull.

Timing Remains Mostly Stable (for now): The fundamental timekeeping provided by the GNSS constellation itself (referenced to its own system time, like GPS Time, or linked to UTC) remains highly stable over just one week. However, converting this precise atomic time to Earth's actual rotational time (UT1), a step needed for certain astronomical or geodetic tasks, becomes less accurate due to the UT1-UTC prediction errors.¹⁸

The Reference Frame Holds (Physically): The TRF, defined by the positions and slow velocities of fundamental stations, doesn't physically drift significantly in just a week. However, our access to this frame via real-time GNSS techniques might be subtly compromised as the predicted orbits, clocks, and EOPs used become slightly less accurate.

Economic Tremors, Not Earthquakes: Direct economic losses at this stage would likely be minimal, confined to niche sectors heavily reliant on real-time, ultra-precise GNSS (e.g., high-frequency surveying for specialized construction, some automated logistics). Minor efficiency dips or project delays might occur, but widespread economic chaos is improbable. While studies estimate a complete GNSS outage could cost the UK £1.4 billion per day⁸⁶, the impact of a one-week geodetic data drought is far less severe, primarily blunting the predictive edge cases rather than undermining core functionality.

In essence, a one-week halt clips the wings of applications flying closest to the sun – those dependent on accurate predictions of Earth's dynamic state. For most users, the lights stay on, the map app still works, and the underlying reference frame remains solid. The economic impact is a ripple, not yet a wave.

Scenario 2: One Month Without Updates – The Foundation Shows Cracks

Fast forward to one month without fresh geodetic data, and the consequences become far more tangible. Significant degradation spreads across the positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) ecosystem, and the first noticeable economic impacts begin to surface.

EOPs Fail for Precision Work: Relying on EOP predictions after a month becomes untenable for any task demanding accuracy. Extrapolating from known prediction decay rates, polar motion errors could approach 10 mas, while UT1-UTC errors might climb to several milliseconds (perhaps 4-5 ms using standard methods).¹⁵ Even advanced prediction techniques falter over this duration.²¹ The critical link needed to transform coordinates accurately between the Earth-fixed TRF and the inertial CRF becomes significantly compromised, jeopardizing any process reliant on this connection.⁸

GNSS Orbits and Clocks Degrade Noticeably: Without the continuous flow of new tracking data, processed against an up-to-date TRF and incorporating accurate EOPs, the quality of GNSS satellite orbit and clock information deteriorates markedly. The ultra-precise products from services like the IGS (boasting ~2 cm orbit accuracy¹⁰) would either cease production or become unreliable ghosts of their former selves. The broadcast ephemeris parameters sent to the satellites themselves, which rely on ground processing tied to the geodetic framework, become increasingly inaccurate. Orbit errors would likely swell beyond the typical few-meter baseline⁶⁰, potentially reaching several meters or more, dragging clock accuracy down with them.

Positioning Accuracy Slips: Standard meter-level GNSS positioning, the kind used by millions daily, would likely degrade noticeably. Its reliability for applications needing consistent performance starts to waver. High-precision (centimeter-level) positioning becomes effectively impossible without access to external correction services that are themselves based on current geodetic data. While differential techniques like RTK might maintain relative accuracy between nearby receivers, their absolute positions tied to the global ITRF would drift, becoming increasingly inconsistent and wrong.

Timing Relationship Blurs: The precisely known relationship between atomic time (UTC/GPS Time) and Earth's rotational time (UT1) becomes lost in the noise, with discrepancies potentially reaching several milliseconds.¹⁵ While the raw timing signal broadcast by GNSS might remain internally consistent relative to the satellites' onboard clocks in the short term, its usefulness for applications needing precise UT1 is severely curtailed. More subtly, the lack of ground segment updates tied to a valid TRF/EOP framework for a month could potentially begin to introduce slight inconsistencies even in the satellite clock corrections relative to a stable UTC realization.

TRF Access Erodes: While the physical TRF changes relatively slowly, our ability to realize and access it accurately via GNSS degrades significantly due to the worsening orbit and clock information. Coordinates calculated for ground stations using outdated or inaccurate satellite data become untrustworthy. The stability of the reference frame, as experienced by users, begins to erode, leading to growing inconsistencies.⁶⁶ The typical sub-centimeter precision achievable for GNSS-derived station positions with continuous processing²⁵ would be lost.

Economic Impacts Begin to Bite: The consequences now translate into real money. Industries built on high-precision GNSS—precision agriculture facing planting errors, construction projects grinding to a halt, surveyors unable to deliver accurate results—face substantial operational disruption and financial losses.⁸⁶ The degrading accuracy of standard navigation begins to impact the efficiency of transportation and logistics, leading to increased fuel consumption, missed delivery windows, and suboptimal routing decisions.⁸⁶ Emergency services might experience slightly longer response times, translating to higher operational costs and potentially impacting public safety outcomes.⁸⁶ While pinpointing an exact figure is difficult, the cumulative daily economic drag across affected sectors could easily begin to mount into the hundreds of millions of dollars or pounds per day as core GNSS services degrade—a significant fraction of the $1-1.5 billion/day impact estimated for a full 30-day outage in some studies.⁹¹

After one month adrift from its geodetic anchor, the PNT system clearly shows the strain. High-precision applications fail, standard positioning becomes less reliable, the integrity of the entire system is compromised, and tangible economic costs start accumulating across a wide swath of the economy. The cracks in the foundation are no longer invisible.

Scenario 3: Six Months Without Updates – Catastrophic Failure

Six months of neglecting the continuous flow of geodetic measurements and updates plunges the entire system into a state of catastrophic failure. The geodetic foundation effectively crumbles, rendering high-accuracy PNT services impossible, severely compromising even standard GNSS operations, and triggering massive economic disruption that would touch nearly everyone.

Total EOP Breakdown: EOP predictions over a six-month horizon are essentially useless for any application needing precision. Errors could balloon to tens of milliarcseconds for polar motion and tens of milliseconds for UT1-UTC.¹⁵ The fundamental mathematical bridge required to transform coordinates between the Earth-fixed TRF and the inertial CRF is irrevocably broken for any practical, accurate work.

Gross GNSS Orbit and Clock Errors: Without updates reflecting the true EOPs and the physically shifting TRF, calculating satellite orbits becomes grossly inaccurate. Errors would likely accumulate to tens of meters, potentially much more. Satellite clock models, unmoored from calibration against a stable and accurately positioned ground network, would drift significantly. The navigation messages broadcast by the satellites would contain dangerously unreliable orbit and clock data.

Loss of Positioning Integrity: While a standard GNSS receiver might still attempt to compute a position, the errors could easily reach tens or even hundreds of meters. More importantly, the reliability would plummet. The system becomes fundamentally untrustworthy for navigation, especially in safety-critical situations like landing aircraft or guiding emergency vehicles. All high-accuracy applications (surveying, precision agriculture, automated machine control) would have ceased functioning long ago.

Severe Timing Disruption: The gap between atomic time scales (like UTC) and Earth's actual rotational phase (UT1) could widen to tens of milliseconds or more, throwing systems reliant on precise Earth orientation knowledge into disarray.¹⁵ More fundamentally, the integrity of the entire GNSS timing system itself could be jeopardized. Without continuous monitoring and calibration from a ground segment operating within a valid geodetic framework (TRF and EOP), inconsistencies between satellite clocks and the overall system time could develop and propagate. This threatens even the basic timing synchronization capabilities relied upon by countless systems, from financial networks to power grids.

TRF Decay and Dissolution: The ITRF isn't just a list of coordinates; it includes velocities describing how stations move, primarily due to plate tectonics.¹² Over six months, typical plate motion adds up to several centimeters.⁵ Using coordinates extrapolated from outdated velocities, or simply using six-month-old coordinates, introduces significant errors purely from the physical movement of the Earth's crust. When combined with the inability to accurately determine current station positions using the now-degraded GNSS signals, the TRF effectively dissolves as a precise, reliable reference system.¹¹ Comparing measurements over time—essential for tracking critical processes like sea-level rise or volcanic deformation—becomes meaningless.¹¹

Economic Catastrophe: The economic consequences would be nothing short of catastrophic, likely mirroring or even exceeding the dire impacts projected in full GNSS outage scenarios. Daily economic losses would almost certainly reach the staggering levels estimated in studies: £1.4 billion/day in the UK, or $1-1.5 billion/day or more in the US.⁸⁶ Critical sectors forming the backbone of modern society—transportation (road, rail, air, maritime), emergency services, energy, telecommunications, finance, agriculture, construction—would face severe operational failures and crippling financial losses.⁶⁷ Supply chains would seize up, safety systems would be compromised, financial transactions could halt. The inability to perform precision agriculture would hit food production, while construction projects nationwide would grind to a halt. The cumulative economic damage over six months would spiral into the trillions of dollars or pounds globally.

Six months of geodetic neglect leads to a systemic breakdown. GNSS becomes a dangerously unreliable guide, precise timing relative to Earth's rotation is lost, the spatial framework underpinning countless technologies ceases to function with meaningful accuracy, and the economic fallout becomes devastating, paralyzing vast segments of modern society. The unseen pillar has crumbled.

| Time | Status | Technical Threshold | Real-World Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11:54 PM | CURRENT STATUS | Fragmentation of PNT authority; R-GPS program cancelled. | System is operational but relies on aging "Gold Standard" legacy assets and shrinking expert oversight. |

| 11:55 PM | 1 WEEK OUT | Earth Orientation Parameters (EOP) forecasts fail. | Centimeter-level precision (PPP/RTK) is lost; autonomous surveying and precision agriculture begin to drift. |

| 11:58 PM | 1 MONTH OUT | Ground segment updates cease; clock/orbit errors swell. | Standard GNSS positioning accuracy drops to >15m; power grid synchrophasors approach timing failure. |

| MIDNIGHT | 6 MONTHS OUT | Terrestrial Reference Frame (TRF) "dissolves". | Systemic collapse. Navigation is dangerously unreliable; estimated $1.5 billion/day economic loss in the U.S. |

Cascading Failures: The Ripple Effect on Satellites and Communications

The degradation of GNSS positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) caused by geodetic stagnation doesn't happen in isolation. Its failure sends shockwaves through a vast network of interconnected systems, crippling other satellite-based services and communication networks that have grown critically dependent on its signals.

Network Timing Synchronization Falters: Modern communication networks, the arteries of our digital world, increasingly rely on the precise time signals from GNSS to keep their nodes synchronized.⁶⁷ This is crucial for everything from managing data flow efficiently in 5G networks to ensuring the quality of your phone calls. As the accuracy and, perhaps more importantly, the consistency of GNSS-derived timing degrades over weeks and months (due to accumulating EOP errors and potential drifts in the satellite constellation's own timekeeping), network performance inevitably suffers. Users might experience this as slower data speeds, increased error rates, dropped connections, or even widespread network instability. The invisible heartbeat provided by GNSS begins to skip.

Earth Observation Data Loses Its Anchor: Satellites constantly watch over our planet, capturing vital imagery, measuring ice sheets, and monitoring atmospheric conditions. But this data is useless unless we know exactly where the satellite was and how it was oriented when the measurement was taken – a process called georeferencing.²² This relies heavily on precise orbit determination (POD), which, as we've seen, is critically dependent on accurate geodetic inputs: the TRF for ground station locations, EOPs for coordinate transformations, and gravity models for orbit dynamics.²² As these inputs degrade significantly (especially over the one-to-six-month timeframe), the resulting orbit inaccuracies translate directly into geolocation errors. An image pixel might be mapped miles from its true location; an altimeter reading meant to track sea level rise becomes meaningless noise. High-resolution data, essential for mapping, environmental monitoring, disaster response, climate science, and resource management, could become unusable, effectively blinding us to changes on our own planet.²²

Other Satellite Operations Compromised: The dependency stretches further. Communication satellites need precise orbit knowledge for efficient station-keeping and antenna pointing. Scientific missions, especially those probing fundamental physics or conducting highly sensitive Earth science measurements, often have extraordinarily stringent POD requirements that are fundamentally tied to the geodetic framework.²³ A decaying geodetic foundation undermines the very ability to conduct these missions and achieve their scientific goals, wasting potentially billions in investment.

The failure cascades: neglecting the geodetic foundation degrades GNSS PNT. This, in turn, cripples the multitude of other satellite services and communication networks that have implicitly built their operations on the assumption of reliable GNSS timing and positioning. The interconnectedness that brings efficiency also creates shared vulnerability.

Table 1: Estimated GNSS Accuracy Degradation vs. Time Without Geodetic Updates

This table details the estimated decline in accuracy for key parameters like EOP predictions, GNSS orbit precision (both precise and broadcast), GNSS clock accuracy, high-precision positioning (PPP/RTK), standard positioning, and UT1 determination over timeframes of 1 week, 1 month, and 6 months without geodetic updates, citing primary causes like prediction errors and lack of calibration.

| Timeframe | Parameter | Baseline Accuracy | 1 Week Out | 1 Month Out | 6 Months Out | Primary Cause |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EOP | Polar Motion (x, y) | ~0.05-0.1 mas | ~2-3 mas | ~10+ mas | >50 mas | Prediction failure |

| EOP | UT1-UTC | ~10-20 µs | ~0.3-0.5 ms | ~5+ ms | >20-30 ms | Rotation variations |

| GNSS Orbit | Precise (e.g. IGS) | ~2 cm RMS | Minor Latency | Significant Error | >10m Gross Error | TRF decay/EOP error |

| GNSS Orbit | Broadcast Ephemeris | ~1-2 m RMS | Minor | Several Meters | Tens of Meters+ | Ground segment lag |

| GNSS Clock | Precise (e.g. IGS) | <0.1 ns RMS | Minor | Unreliable | Gross Inconsistency | Calibration loss |

| Positioning | High-Precision (RTK) | cm-level | dm-level drift | Impossible | Catastrophic Failure | Cumulative errors |

| Positioning | Standard Standalone | ~1.5-5 m | Negligible | ~5-15 m | >100 m Error | Broadcast inaccuracies |

| Timing | System Time | ~10-20 ns | Stable | Minor Drift | Unstable Instability | Atomic clock drift |

Note: Degradation values are estimates based on cited sources and analysis; actual impact depends on specific systems and conditions. "mas" = milliarcseconds, "ms" = milliseconds, "ns" = nanoseconds, "µs" = microseconds.

This stark progression reveals a clear pattern: the immediate pain hits applications living on the predictive edge, particularly those needing accurate EOP forecasts, which falter within days. Over weeks to a month, the core accuracy of GNSS itself degrades significantly as orbit and clock products decay, impacting all users. The reference frame itself, the bedrock TRF, erodes more slowly due to physical processes like plate motion, but this decay over months is fundamental, eventually invalidating the entire system.⁵ And while the raw timing signal from GNSS remains stable relative to atomic clocks initially, the crucial link to our planet's actual rotation (UT1) breaks down rapidly as EOP predictions fail.¹⁵

The Mirage of Commercial Resilience.

Current shifts toward Commercial LEO PNT (Low Earth Orbit Positioning, Navigation, and Timing) are often framed as a solution to government program cuts.

However, commercial constellations are not a substitute for geodetic infrastructure; they are high-tech "houses of cards" built upon it.

Every commercial satellite requires the same Terrestrial Reference Frame (TRF) and Earth Orientation Parameters (EOP) to function.

Outsourcing the delivery of PNT to the private sector without funding the underlying geodetic "Map of the Earth" merely masks the decay of the foundation.

Consequences of Stagnation: Flickering Lights – The Impact on the Electric Grid

The Need for Speed (and Accuracy): Synchrophasors and Grid Stability

The stability of the North American power grid hinges on seeing the entire system in near-perfect unison. This is achieved using Phasor Measurement Units (PMUs), or synchrophasors, which act as high-speed sensors for the grid. The governing standard, IEEE C37.118, requires these devices to be synchronized to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) with an accuracy of one microsecond (1μs). This extreme precision allows operators to detect and counteract disturbances before they cascade into blackouts. The primary, and in many cases only, source for this continent-spanning, microsecond-level timing is GNSS.

While PMUs receive their timing signals from GNSS satellites, the reliability of those signals is anchored in the global geodetic infrastructure. The precise orbits of GNSS satellites and the timing corrections they broadcast are calculated using the Terrestrial Reference Frame (TRF) and Earth Orientation Parameters (EOPs). Stagnation in geodetic investment doesn't trigger an immediate failure. Rather, it introduces a slow, insidious drift.

The risk grows over time. As the foundational geodetic inputs become outdated, the calculated satellite positions and clock corrections begin to diverge from reality. This growing inaccuracy isn't caused by a single data point like EOP prediction alone, but is compounded by a broader loss of calibration and monitoring across the entire global geodetic system. Initially, this degradation would be imperceptible. However, over time, the accumulating errors in the GNSS signals would cause the timing at PMUs across the grid to drift, eventually breaching the critical one-microsecond threshold. At that point, the synchrophasor data becomes unreliable or, worse, dangerously misleading, blinding operators and increasing the risk of widespread outages.

The Grid's Timekeeper: Relying on GNSS-Derived UTC

The modern electrical grid is a continent-spanning machine requiring synchronization at a level of precision that is difficult to overstate. According to the North American Synchrophasor Initiative (NASPI), grid operators rely on synchrophasors—devices taking high-speed snapshots of the grid’s health—that must be synchronized to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) with an accuracy of one microsecond (one millionth of a second). These hyper-precise, time-aligned measurements are essential for monitoring grid stability, preventing blackouts, and integrating fluctuating renewable energy sources. Any significant timing error could lead to a catastrophic misinterpretation of grid conditions.

To achieve this level of synchronization, virtually all modern grid monitoring systems rely on timing signals from Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) like GPS. These satellites carry atomic clocks that provide a direct, cost-effective link to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), the world's time standard. This dependency makes GNSS the de facto timekeeper for North America's critical infrastructure. Yet, many grid operators remain unaware that their critical timing systems are ultimately anchored in geodetic infrastructure—a blind spot that poses a serious governance and resilience risk.

This reliance is not absolute in the short term, as many facilities have built-in safeguards. While some systems use backup clocks or local synchronization protocols (like PTP or IRIG-B) to maintain short-term stability, these methods ultimately rely on periodic correction from global GNSS time, which itself depends on current geodetic models. These backups can bridge a brief outage, but they cannot correct for the slow, systematic drift that would be introduced by a degrading geodetic reference frame. They are a temporary buffer, not a long-term substitute for a stable, globally consistent time source.

When Time Slips: The Perils of Microsecond Drift

What happens if the GNSS-derived time signal feeding the PMUs drifts beyond that critical microsecond threshold? The consequences for grid monitoring, stability, and ultimately, the reliability of our power supply can be severe. Such drift is a plausible outcome if the underlying geodetic framework degrades over months, impacting EOP accuracy (needed for precise UTC realization) or potentially introducing long-term instabilities in the satellite clocks themselves.

Data Becomes Corrupt, Visibility Lost: When PMU timestamps lose their microsecond accuracy relative to UTC, the measurements become unreliable for system-wide analysis.⁷⁴ The PDCs that collect the data are designed to spot inconsistencies; measurements with bad timestamps get flagged or simply thrown out.⁷² This creates holes in the data stream, effectively blinding operators to conditions in parts of the grid they are sworn to protect.

Situational Awareness Evaporates: The very purpose of synchrophasors—providing a time-synchronized, system-wide view—is defeated by inaccurate timing.⁷² Operators lose the ability to accurately track phase angle differences (a key stress indicator), monitor potentially dangerous oscillations between generators, or verify that their computer models reflect reality. This loss of situational awareness dramatically increases the risk of misjudging grid conditions or failing to see an impending crisis until it's too late.

Automated Controls Can Fail: Increasingly sophisticated grid control and protection systems, known as Remedial Action Schemes (RAS), are being designed to use synchrophasor data as inputs.⁷⁷ These systems often have built-in safety checks for data quality, including timing accuracy. If the timing signal degrades, these automated guardians may block themselves or malfunction, failing to take crucial protective actions during a disturbance. This inaction could turn a localized problem into a cascading blackout.⁷⁷

Learning from Failure Becomes Harder: Accurate, time-stamped recordings are indispensable for piecing together what happened during major grid failures or blackouts.⁷⁵ Without reliable timestamps, reconstructing the sequence of events becomes a forensic nightmare, potentially impossible.⁷⁵ This cripples efforts to identify the root causes, improve grid models, and design effective strategies to prevent future catastrophes.⁷⁵

In short, losing microsecond-level timing accuracy—a potential consequence of geodetic neglect impacting GNSS performance or UTC realization—directly sabotages the advanced tools grid operators rely on. It degrades visibility, disables automated protections, and ultimately increases the risk to the stability and reliability of the power supply millions depend on.

Grid Impacts Unfolding: Week, Month, Six Months

How quickly would geodetic stagnation translate into dangerous timing errors for the power grid? We need to consider how the decay of GNSS PNT (especially EOP accuracy and potential long-term clock drift) affects the delivery of microsecond-accurate UTC.

One Week: The direct impact on UTC time transfer via GNSS is likely minimal. While UT1 predictions are already less accurate¹⁵, the difference between the GNSS system time and the broadcast UTC(USNO) remains stable at the nanosecond level. PMU timing should comfortably stay within the 1 µs tolerance. The main effect might be a slight erosion of confidence among highly informed operators aware of the data halt, but operational impacts and economic costs are negligible. The lights stay on.

One Month: The situation becomes more concerning. Significant EOP prediction errors (several milliseconds for UT1¹⁵) raise theoretical questions about the integrity of the disseminated UTC scale relative to Earth's rotation, though the impact on the time signal relative to atomic standards is probably still small. More critically, the lack of ground segment updates tied to a valid geodetic framework for a month could potentially introduce subtle drifts or inconsistencies in the satellite clock corrections broadcast by GNSS. Quantifying this precisely is hard without detailed modeling, but the risk increases that timing errors could start nudging towards, or in some locations exceeding, the crucial 1 µs PMU threshold. This could trigger intermittent data quality flags, causing some PMU data to be discarded⁷³ and beginning to degrade the completeness of the operators' wide-area view. This translates to increased operational risk and potential minor economic impacts from less efficient grid management, but large-scale blackouts are not yet the primary concern.

Six Months: The situation turns critical. Gross EOP errors¹⁵ combined with the significant potential for drift and inconsistencies within the GNSS constellation's own timing system (due to the prolonged absence of ground calibration tied to a valid TRF/EOP) make it highly probable that reliable microsecond-level UTC synchronization via GNSS is lost. Synchrophasor networks across the grid would likely become largely non-functional as PMU data systematically fails timing checks.⁷⁴ This represents a catastrophic loss of real-time visibility for grid operators, severely impairing their ability to monitor stability and react effectively to disturbances. While less demanding timing needs (like the ±2 ms for disturbance recorders⁷⁶) might still be met by backup systems (like network time protocol or local oscillators), the vital capability provided by synchrophasors vanishes. This significantly elevates the risk of large-scale blackouts, events that carry enormous economic price tags (billions per event), adding substantially to the already devastating economic disruption caused by the broader failure of GNSS in other sectors. The most demanding applications, like fault locators needing nanosecond accuracy⁷⁷, would also fail.

The electric grid's thirst for the highest levels of timing precision makes it acutely vulnerable to the degradation cascade triggered by geodetic stagnation. While backups might handle less demanding tasks for a while, the loss of microsecond accuracy over months effectively disables the most advanced monitoring tools essential for modern grid reliability, carrying the immense potential economic cost of widespread blackouts.

Table 2: Electric Grid Application Timing Requirements vs. Projected Accuracy Degradation

This table compares the timing accuracy requirements (vs UTC) for various grid applications like Synchrophasors, Disturbance Monitoring, Time-Synchronized Control, and Travelling Wave Fault Location against the projected accuracy degradation achievable via GNSS after 1 week, 1 month, and 6 months of geodetic stagnation. It would also list the consequences if requirements are not met.)

| Grid Application | Required Accuracy | Primary Source | 1 Week Out | 1 Month Out | 6 Months Out | Consequence of Failure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synchrophasors / PMUs | ~1 µs | GNSS | Negligible | Approaching Threshold | Threshold Exceeded | Loss of situational awareness; grid instability risk. |

| Disturbance Monitoring | ±2 ms | GNSS / NTP | Negligible | Negligible | Likely Met (Backups) | Difficulty in post-event analysis if backups fail. |

| Time-Synchronized Control | ~1 ms | GNSS / PTP | Negligible | Negligible | Likely Met (Backups) | Control actions may be uncoordinated; potential instability. |

| Traveling Wave Fault Location | ~50-100 ns | GNSS / PTP | Negligible | Approaching Threshold | Threshold Exceeded | Inaccurate or failed fault location for grid repair. |

Note: Projected accuracy degradation refers to the likely accuracy achievable via GNSS under the stagnation scenario. Backup systems like PTP or stable local oscillators may provide resilience for some applications but often rely on GNSS for initial or periodic synchronization.

Consequences of Stagnation: Lost in Space – The Impact on Satellite Operations

The Need for Precision Navigation in Orbit: POD Requirements

Knowing exactly where a satellite is and where it's going—its orbit—is the fundamental starting point for almost everything we do in space.⁶⁸ This knowledge comes from Precise Orbit Determination (POD), a complex process blending tracking measurements from ground stations (or other satellites) with sophisticated mathematical models of all the forces acting on the spacecraft.

The accuracy needed varies dramatically depending on the satellite's job:

Earth Observation: Satellites taking pictures (optical or radar) or sensing atmospheric conditions need accurate orbits to pin their data to the correct location on Earth – a process called geolocation.⁶⁸ Without it, a picture of a city could be mapped miles away.

Satellite Altimetry: Missions measuring the height of the sea surface, ice sheets, or land (like the Jason series, ICESat, or Sentinel satellites) have incredibly demanding needs. They often require orbit accuracy in the radial direction (up/down) at the centimeter level or even better. Any error in the satellite's altitude directly translates into an error in the measured sea level or ice thickness, potentially masking or mimicking the very climate change signals they are designed to detect.²² Long-term stability of these orbits is also paramount for tracking changes like sea level rise over decades.²²

Satellite Gravimetry: Missions designed to map Earth's gravity field in exquisite detail (like CHAMP, GRACE, GOCE) use the tiny perturbations in their orbits (or the changing distance between pairs of satellites) as their primary data.²³ The accuracy of the gravity maps they produce is directly tied to how well we can determine their orbits and model the forces involved.

Navigation Satellites (GNSS): The accuracy of GPS and other systems relies fundamentally on knowing the precise orbits of the navigation satellites themselves. These orbits are calculated by the system's control segment using global tracking data tied to the geodetic framework.¹

Communications Satellites: While perhaps less stringent than scientific missions, communication satellites still need accurate orbit knowledge for efficient station-keeping (staying in their assigned slot) and precise antenna pointing to serve users on the ground.

Scientific Missions: Spacecraft testing fundamental physics (like the LARES satellite testing Einstein's theory of General Relativity⁷⁰) or making other ultra-precise measurements often push the boundaries of POD, demanding the highest possible accuracy.

Achieving the centimeter-level precision required by many modern missions has only been possible through relentless improvements in tracking systems (like SLR, DORIS, and onboard GNSS receivers) and continuous advancements in modeling both gravitational forces (Earth's complex gravity field, the pull of the Sun and Moon) and subtle non-gravitational forces (like atmospheric drag, the pressure of sunlight, and radiation reflected or emitted by Earth).²²

The Geodetic Pillars of Satellite Dynamics: Gravity, TRF, and EOPs

The quest for accurate satellite orbits is inextricably bound to the quality of the underlying geodetic framework and models. You simply cannot determine an orbit precisely without them.

Gravity Field Models: Earth's gravity is the maestro conducting the orbital dance. Accurate POD demands precise models of this field, including its static structure and how it changes over time due to mass shifting within the Earth system (like melting ice or moving water).²² These gravity models are themselves products derived from geodetic analysis and dedicated satellite gravity missions. Using an outdated or inaccurate gravity model is a primary source of orbit error.

Reference Frames (TRF & CRF): POD involves connecting tracking measurements made from Earth (or by onboard receivers) to the satellite's path through space. This requires two critical reference frames:

A Terrestrial Reference Frame (TRF), like ITRF, providing the precise coordinates of the tracking stations on the ground.⁷ Errors in knowing where the tracking station is directly translate into errors in calculating the satellite's orbit.

A stable, well-defined Celestial Reference Frame (CRF), like ICRF, which acts as the quasi-inertial backdrop against which the satellite's equations of motion are solved.³ Crucially, the TRF itself is built using data from the very techniques (SLR, VLBI, GNSS, DORIS) that track satellites, creating a fundamental interdependence.⁷

Earth Orientation Parameters (EOP): EOPs are the essential translators between the Earth-fixed TRF (where the tracking stations are) and the inertial CRF (where the satellite moves).⁸ Accurate, high-resolution EOPs are needed to correctly account for the apparent motion of the ground stations as seen from space due to Earth's rotation, and to relate ground-based measurements to the satellite's inertial trajectory. Errors in EOPs directly inject errors into the orbit determination process.⁶⁹

Non-Gravitational Forces: Even modeling subtle forces like atmospheric drag or the push of sunlight depends on the geodetic framework. Calculating these forces requires knowing the satellite's orientation (attitude) and the directions to the Sun and Earth, all defined relative to the established reference frames.²²

Therefore, precise satellite orbit determination is fundamentally impossible without the continuous supply of accurate gravity models, a stable and precise TRF, and up-to-date EOPs—all core products delivered by the global geodetic infrastructure. A breakdown in providing any of these directly compromises our ability to know where satellites are. This highlights a critical feedback loop: geodesy needs satellite tracking data to maintain its framework, and satellite missions desperately need the geodetic framework to determine their orbits and achieve their goals.⁷

The Fallout: Impacts on Earth Observation, Communication, and Science

When POD accuracy degrades due to geodetic stagnation, the consequences ripple outwards, impacting a vast array of satellite applications vital to science, commerce, and safety.

Earth Observation and Altimetry Blinded: For remote sensing missions, inaccurate orbits mean the data gets assigned to the wrong place on Earth – geolocation errors.⁶⁸ Pixels in an image are misplaced; sensor footprints wander. For altimetry missions measuring heights, the impact is devastating. Orbit errors directly contaminate the measurements of sea level, ice thickness, or land topography.²² An orbit error of just a few centimeters—easily caused by degraded geodetic inputs—can completely mask or mimic the subtle signals of climate change, like sea level rise or ice melt, rendering decades of data unreliable for tracking these critical trends.²² Analysis of the Jason altimetry satellites, for instance, showed that improving how the satellite's orientation was modeled relative to the reference frame significantly improved the consistency and accuracy of the orbit determination.²²

Gravity Missions Invalidated: Missions specifically designed to map Earth's gravity field, like GOCE and GRACE, are fundamentally dependent on ultra-precise orbits or measurements directly tied to the geodetic framework.²³ If the underlying geodetic models (gravity, TRF, EOP) degrade, the scientific output of these costly and complex missions becomes invalid.

Communications Disrupted: While perhaps less acutely sensitive than scientific missions, significant errors in predicting communication satellite orbits could impact operational efficiency. Maintaining the correct orbital slot (station-keeping) and ensuring antennas point accurately rely on reliable orbit knowledge. Increased orbit uncertainty might force operators to use larger fuel margins or could lead to degraded signal quality for users on the ground.

Scientific Discovery Hindered: High-profile missions pushing the frontiers of physics (like LARES measuring relativistic effects⁷⁰) or making other ultra-precise measurements are often acutely sensitive to the accuracy of gravity models and the stability of the geodetic reference frames. Geodetic degradation directly undermines the ability of these flagship missions to achieve their demanding scientific objectives, potentially stalling discovery.

The damage extends beyond immediate operational headaches. The immense scientific value derived from long-term, continuous satellite observations—creating vital climate data records spanning decades—depends fundamentally on the stability and consistency of the geodetic reference frame over those long periods.¹¹ Neglecting the geodetic foundation, even temporarily, can inject irreparable breaks and inconsistencies into these irreplaceable long-term datasets, compromising our understanding of our changing planet.

Time-Based Degradation Scenarios: Watching Satellite Accuracy Fade

The impact of geodetic stagnation on satellite operations wouldn't be instantaneous but would manifest progressively, carrying associated economic costs through lost data value, mission failures, and wasted investment.

One Week: The impact on most routine POD would be minimal. Orbit determination centers typically use data spanning several days or weeks⁶⁹, so a few days of slightly less accurate EOP predictions have limited effect on solutions dominated by historical data. The TRF and gravity models are effectively static over this brief interval. Only applications needing extremely rapid or real-time orbit estimates might see minor degradation due to EOP prediction errors.¹⁵ Direct economic impact is negligible; the value of most satellite data isn't significantly compromised yet.

One Month: The effects start to become noticeable. EOP prediction errors are now large enough¹⁵ to begin degrading the accuracy of POD solutions that rely heavily on recent data. Routine processing might show slightly increased noise or biases creeping in. While the TRF itself drifts slowly, the lack of updated solutions from geodetic analysis centers means potential inconsistencies between the official frame and reality might start accumulating, subtly affecting POD results. Economic impacts begin to surface through reduced reliability of Earth observation data. For instance, slight degradation in altimetry data could introduce uncertainties impacting ocean current forecasts used for shipping or fisheries—an initial, though likely small, economic cost. Minor geolocation errors in imagery might slightly reduce the efficiency of precision agriculture or resource mapping.

Six Months: The impact becomes severe and widespread. EOPs are now hopelessly unreliable for precise work.¹⁵ The TRF has physically drifted several centimeters due to unmodelled plate tectonics, and the lack of updated station coordinates means the frame used for POD is significantly wrong.⁵ While gravity models themselves might not have degraded substantially, the inability to accurately determine orbits using the compromised TRF and EOPs prevents their validation or refinement. Consequently, POD accuracy for virtually all satellites needing precision would degrade dramatically, likely plummeting to the meter level or worse. High-precision missions (altimetry, gravity, fundamental physics) would become impossible to conduct meaningfully, representing a staggering loss of scientific investment and the future economic benefits derived from their data.²² Earth observation data would be largely unreliable for applications demanding accurate geolocation (mapping, disaster response, environmental monitoring), leading to substantial economic inefficiencies, poor resource management decisions, and potentially increased costs from inaccurate weather forecasts or disaster impact assessments. Even routine communication satellite operations could face reduced efficiency due to large orbit uncertainties. The cumulative economic cost from invalidated satellite data and failed missions would add significantly to the overall economic devastation caused by geodetic neglect.

Table 3: Satellite Mission Requirements vs. Geodetic Input Degradation

This table compares the typical accuracy requirements (e.g., POD accuracy, stability) for various satellite mission types like Altimetry, Imaging, Gravity Mapping, GNSS, Communications, and Fundamental Physics against the qualitative impact assessment (Negligible, Minor Degradation, Significant Error, Data Unusable/Mission Failure Risk) after 1 week, 1 month, and 6 months of geodetic stagnation.)

| Mission Type | Geodetic Dependency | Typical Requirement | 1 Week Out | 1 Month Out | 6 Months Out |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radar/Laser Altimetry | POD Accuracy (Radial) | ~1-3 cm orbit | Negligible | Minor Degradation | Data Unusable / Mission Failure |

| SAR / Optical Imaging | Geolocation Accuracy | Meter to sub-meter | Negligible | Minor Degradation | Significant Geolocation Error |

| Gravity Mapping (GRACE) | POD & Gravity Model | cm-level POD | Negligible | Significant Error | Critical Mission Failure |

| GNSS Constellation | POD, TRF, EOP | cm-orbit, ns-clock | Negligible | Significant Degradation | Gross System Error |

| Communications (GEO) | Orbit Control | Station keeping | Negligible | Minor Impact | Moderate Efficiency Loss |

| Fundamental Physics | Gravity Model / POD | mm-cm POD | Negligible | Significant Error | Scientific Mission Failure |

Note: Impacts are qualitative assessments based on the degradation timelines established for geodetic products (TRF, EOP, Orbits).

The Economic Fallout: Counting the Cost of Looking Away

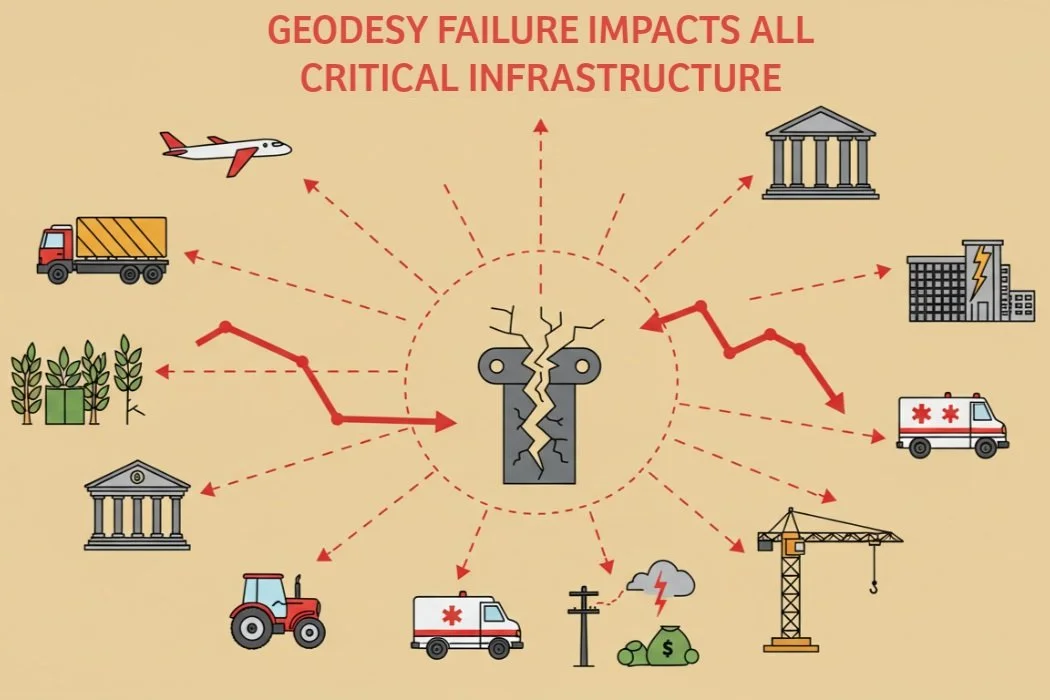

The technical failures triggered by geodetic stagnation—faltering GNSS, unreliable timing, inaccurate satellite data—aren't just abstract problems. They translate directly and brutally into staggering economic costs. These costs arise from system breakdowns, service outages that paralyze activity, crippling reductions in efficiency, and chilling safety implications across countless sectors of the economy.

These economic stakes aren’t confined to government operations. From logistics and agriculture to finance and telecom, the private sector is deeply reliant on geodetic integrity—yet often unaware of the foundational systems at risk. Coordinated investment and contingency planning across public and private domains will be essential to minimize this exposure.

Direct Costs: When the Systems We Rely On Break

Trying to put a price tag on losing the foundational PNT services provided by GNSS is difficult, but studies modeling hypothetical outages paint a terrifying picture of the potential scale of economic destruction.

The Price of a GNSS Outage: A 2021 UK government report estimated that losing GNSS nationwide for just seven days would cost the economy approximately £7.6 billion. A single 24-hour outage was pegged at £1.4 billion.⁸⁶ The hardest-hit sectors? Emergency services, road transport, and maritime operations – together accounting for nearly 88% of the projected week-long loss.⁹⁰ Across the Atlantic, a 2019 study sponsored by the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) estimated that a 30-day GPS outage could cost 10 key U.S. industries $45 billion, averaging a staggering $1.5 billion per day.⁹¹ An earlier version of this study suggested $1 billion per day, a figure some criticized as potentially too low because it assumed alternatives would quickly emerge and excluded defense impacts.⁸⁸

Geodetic Failure as a Slow-Motion Outage: While these studies model sudden GNSS outages, the scenario of prolonged geodetic neglect leads to something arguably more insidious: a progressive degradation culminating in a functional failure of GNSS for any application demanding precision and reliability. Over a period of months (as detailed in Section II.D), the impacts—gross orbit errors, unreliable timing, loss of positioning integrity—would render GNSS unusable for many critical functions. For those users, the effect is the same as an outright outage. Therefore, those multi-billion pound/dollar per day or week loss estimates serve as a chillingly relevant, perhaps even conservative, proxy for the economic devastation unleashed by failing to maintain our geodetic infrastructure over several months.

Tangible Service Disruptions: The technical failures manifest as real-world service interruptions with immediate economic consequences:

Energy: Failure of synchrophasor networks due to timing loss dramatically increases the risk of grid instability and potentially multi-billion dollar large-scale blackouts.⁷²

Transportation: Degraded GNSS cripples navigation, fleet management, and safety systems across road, rail, air, and sea, leading to costly delays, wasted fuel, snarled supply chains, and increased accident risk.⁸⁶

Emergency Services: The inability to accurately locate people in distress or dispatch and navigate responders leads to critical delays and reduced effectiveness, with potentially tragic human and economic costs.⁸⁶

Telecommunications: Network timing failures degrade service quality, leading to dropped calls, data errors, and reduced network capacity, impacting business and personal communication.⁶⁷

Finance: Disruption to the precise time stamping required for high-speed trading and regulatory compliance can halt markets or incur hefty penalties.⁶⁷

Agriculture: Loss of precision guidance for tractors and sprayers slashes crop yields and inflates costs for fuel, seed, fertilizer, and pesticides.⁸⁶

Construction & Surveying: The inability to perform accurate positioning brings projects to a standstill or introduces errors requiring expensive rework.²

Satellite Services: Unusable Earth observation data hampers weather forecasting, resource management, and environmental monitoring. Communication satellite disruptions affect broadcasting and connectivity.

The direct costs explode because the systems and services utterly dependent on GNSS simply stop working correctly once the underlying geodetic foundation degrades beyond critical thresholds—typically within the one-to-six-month timeframe. The sheer breadth of vital sectors impacted underscores our pervasive, yet often unacknowledged, societal reliance on geodesy.²⁶

Indirect Costs: Efficiency Lost, Safety Compromised, Innovation Stifled

Beyond the immediate shock of system failures, geodetic stagnation imposes immense indirect economic burdens that accumulate over time.

Bleeding Efficiency: Beyond direct failures, a degrading geodetic framework imposes a quiet, pervasive tax on the economy by inhibiting efficiency. In sectors from precision agriculture and automated construction to logistics and resource management, optimal performance relies on precise positioning. As the reliability of this positioning degrades, efficiency is lost—planting is less exact, construction requires more manual checks, and supply chains lose optimization.

This erosion of efficiency directly impacts international competitiveness. Nations that maintain a state-of-the-art geodetic foundation empower their industries to operate at peak performance, giving them a significant advantage in the global market. Furthermore, a failure to invest in and control one's own geodetic capacity raises critical issues of data sovereignty. A nation that cannot independently define its own "ground truth" may become strategically dependent on other countries or commercial entities for the foundational data that underpins its entire economy, creating a subtle but profound long-term vulnerability.

The decision to bump established contractors like Astrion from modernization efforts reflects a broader fragmentation of authority. As the military retreats from rapid PNT innovation, the U.S. risks ceding its status as the global "geodetic anchor" to international competitors like Europe’s Galileo or China’s BeiDou. This transition doesn't just impact maps; it creates a Strategic Sovereignty Gap, where the U.S. may eventually rely on foreign or commercial "ground truths" to calibrate its own national security infrastructure.

Furthermore, current shifts toward Commercial LEO PNT (Low Earth Orbit Positioning, Navigation, and Timing) are often framed as a solution to government program cuts. However, commercial constellations are not a substitute for geodetic infrastructure; they are high-tech "houses of cards" built upon it. Every commercial satellite requires the same TRF and EOP to function. Outsourcing the delivery of PNT to the private sector without funding the underlying geodetic "Map of the Earth" merely masks the decay of the foundation.

Putting Safety at Risk: Accurate PNT is woven into safety systems across many domains. Degraded navigation increases risks in aviation (especially during landing), at sea (collision avoidance), on railways (train control), and on our roads (emergency response, future autonomous vehicles).⁸⁶ Failures in coordinating emergency services due to PNT issues have direct, life-or-death consequences for public safety.⁸⁶ The increased risk of power grid failures also carries significant safety implications for communities and critical facilities.⁶⁷

Choking Off Innovation: Future economic growth will be driven by technologies that merge the digital and physical worlds—autonomous vehicles, drone delivery services, smart city management, and augmented reality. The development and safe deployment of these innovations are fundamentally dependent on a highly accurate, reliable, and universally accessible geodetic reference frame. A stagnant or degrading infrastructure creates uncertainty and risk, acting as a powerful disincentive for private sector investment in these next-generation systems. Falling behind in geodetic capabilities doesn’t just limit domestic innovation; it cedes strategic advantage to nations that invest more aggressively in sovereign geospatial infrastructure and data control.

These indirect costs—lost efficiency, compromised safety, and stifled innovation—pile onto the direct costs of service outages, painting a grim picture of the pervasive economic damage caused by neglecting the geodetic foundation that makes reliable PNT possible.

Sector-Specific Pain Points

The economic devastation resulting from geodetic failure and the subsequent PNT degradation would cascade through nearly every critical infrastructure sector. To ensure the long-term stability and integrity of the geodetic infrastructure that underpins our economy and security, a concerted effort is required. The following actions are essential for building a more resilient and sustainable foundation:

Emergency Services: Among the hardest hit, relying utterly on PNT for locating incidents, dispatching help, and guiding responders. Delays and inefficiencies translate directly into higher costs and potentially tragic outcomes. This sector consistently accounts for a huge slice of estimated economic losses in outage studies.⁸⁶

Transportation (All Modes): Road, rail, air, and maritime sectors all lean heavily on GNSS for navigation, logistics optimization, and increasingly, safety and automation. Impacts range from massive time and fuel losses and supply chain chaos to compromised safety systems. Aviation faces specific threats to routing, landing capabilities, and drone operations.⁹⁰

Energy (Electric Grid): As detailed earlier, the loss of precise timing cripples advanced monitoring (synchrophasors), severely impairing grid control and dramatically increasing the risk of costly, disruptive blackouts.⁷² The U.S. Department of Energy explicitly flags the sector's critical PNT dependency.⁷⁸

Telecommunications: Network synchronization, vital for quality and capacity, relies on precise timing, often from GNSS. Degradation leads to poorer service, dropped connections, and network instability.⁶⁷